Jeeves & The King of Clubs

‘A most thrilling return of Wodehouse’s

Jeeves and Wooster . . . it vibrates with the

spirit and the rhythms of his heart.’

‘Impossible to read without grinning idiotically.’

‘Schott . . . captures His Master’s Voice and, above all, the famous Wodehouse rhythm . . .

On reading this work, the Wodehouse estate must surely be left purring, as Bertie would

to Jeeves with the talents that famously won

him a prize for scripture knowledge:

“Well done, good and faithful servant.”.’

‘Just imagine the boost to British prestige,

not to mention morale, if the sang-froid of

Bond and the sunniness of Bertie could be blended in one person! . . . [In] a fizzy new homage to Wodehouse, Schott infuses Bertie with extra bounce, transforming him from

sheer pleasure seeker to shrewd (sort of)

secret agent — no wardrobe change necessary.’

‘A bravura performance that twinkles

with energy, puns and wisecracks . . .

Schott has hit the target.’

‘The cast is a delight, with many characters

who will be familiar to Wodehouse aficionados

. . . Schott handles the Jeeves and Wooster set-piece dialogues with admirable ease . . . his prose is elegant and charming, and he captures the lilt and rhythms of the original . . . for lovers of [Wodehouse’s] work who are looking for a winter treat, Schott’s novel is a warm, worthy and rollicking tribute.’

‘Schott pulls the trick off improbably well.

He reproduces the Wodehouse voice with fetishistic accuracy: the casual abbreviations (“the milk of h.k.”) and florid similes (“Florence tilted her head, like a cat puzzling a human meow”) and creative idioms (a nap is referred to as “checking the eyelids for holes”) . . . And his dialogue is perfectly inane. “What’s the thing to thing, Jeeves, that’s thinged with those thingummies?” the narrator asks at one point — to which the omniscient Jeeves responds, of course, that the road to hell is paved with good intentions.’

‘Schott excels with a series of similes and

metaphors every bit as striking as those

Wodehouse came up with . . . a delight to read’

‘Schott’s brilliant homage . . . Jeeves

and the King of Clubs is an “oojah-cum

spiff” tale of spies and state secrets.

. . . This joyous and thoughtful tribute

leaves you wanting more.’

‘By Jove! It's a ripping old yarn . . .

dashed agreeably close to the master.’

‘It is hard not to warm to this hugely

entertaining homage to The Master.’

‘A glorious homage . . .

Undeniably an impressive, hugely

enjoyable feat of ventriloquism.’

‘Schott’s style impressively captures the

linguistic playfulness that always makes

Wodehouse such a joy to read . . .

Highly recommended.’

‘A smart, often hilarious caper that turns the duo into international spies and reminds us why Wodehouse’s characters became beloved in the first place.’

‘Schott . . . has risen to the challenge of writing in the style of P. G. Wodehouse with, er, spiffing aplomb.

Plum . . . would have approved.’

‘Schott is a wonderful, exacting mimic: Bertie Wooster and his valet, Jeeves, could almost be mistaken for themselves, their exchanges sparkling and unexpected, giving real verve to this joyful, loving, humble and worthwhile homage.’

‘A true delight to read.’

‘Schott’s homage is the best possible revival

of Wodehouse’s exquisite universe.’

Storm clouds loom over Europe.

Treason is afoot in the highest social circles.

The very security of the nation is in peril.

Jeeves, it transpires, has long been an agent of British Intelligence, but now His Majesty’s Government must turn to the one man who can help . . . Bertie Wooster.

In this magnificent new homage to P. G. Wodehouse – authorized by the Wodehouse Estate – Ben Schott leads Jeeves and Wooster on an uproarious adventure of espionage through the secret corridors of Whitehall, the sunlit lawns of Brinkley Court, and the private clubs of St James’s.

We encounter an unforgettable cast of characters – old and new – including outraged chefs and exasperated aunts, disreputable politicians and gambling bankers, slushy debs and Cockney cabbies, sphinx-like tailors, and sylph-like spies.

There is treachery to be foiled, naturally, but also horses to be backed, auctions to be fixed, engagements to be escaped, madmen to be blackballed, and a new variety of condiment to be cooked up.

Jeeves & The King of Clubs is essential reading

for aficionados of The Master, and a perfect introduction to the joys of Jeeves and Wooster for those who have never before dipped their toe.

Purchase Jeeves & The King of Clubs

Listen to Lulu Garcia-Navarro’s NPR interview

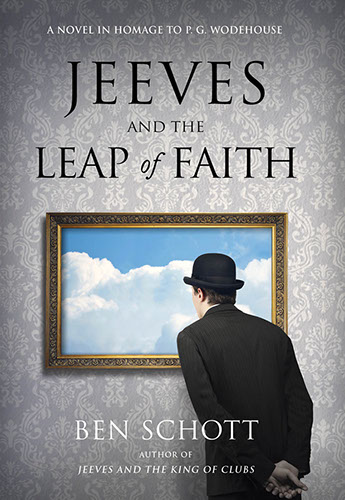

Jeeves & The Leap of Faith

“This homage to P.G. Wodehouse is so good that a blind reading

(i.e. a genuine ‘Plum’ versus Schott’s pastiche) would be a tricky call.

Everything is in its place: Jeeves shimmers, aunts scheme, Drones drone. Even the style is spot-on: the erudition of Schott’s various Miscellanies finds expression as similes and quotations of hilarious ingenuity.

Only in the plot is there evidence of Another’s Hand: the academic setting of 1930s Cambridge and the politics with the Mosley-esque ‘Blackshorts’ both mark out uncharacteristically cerebral Wooster territory.

But the sheer luxury, wealth and self-assurance of Bertie’s world is brilliantly evoked with all its enviable light-heartedness intact.

A masterpiece in every sense.”

U.K. Edition

U.S. Edition

“Marvelously madcap, brimming over

with silly quips, cunning crossword

clues and perilous plot complications.

A tonic for these testing times.”

“Though whimsy this year might seem out of place, Ben Schott’s latest Wodehouse-homage, Jeeves and the Leap of Faith (Hutchinson), is once again pastiche perfect. Tinkerty-tonk.”

— Ian Sampson · Books of 2020

“As dazzling as his first, with brilliant puns and laugh-out-loud prose. Everything one expects from Wodehouse is here: an outlandish plot, beloved characters, a Wooster aunt on the matrimonial warpath, gambling, nightclubs, and, inevitably, Jeeves to the rescue. … A perfectly frothy concoction for invoking joy and laughter. … VERDICT: It’s a fizzer, chaps. An absolute corker.”

“Schott writes in a distinctive style that is somewhere between homage and postmodern response and his story – Bertie attempts to save the Drones Club from bankruptcy while continuing his haphazard work as a secret service freelancer – is more eventful and action-packed than Wodehouse would ever have countenanced. The laughs keep coming, the pivotal character of Iona McAuslan is far better drawn than any woman in the originals and it ends on a splendid cliffhanger.”

“Schott’s book is a combination of the old and new, done with panache and wit. … The novel concludes on a humdinger of a twist which makes one hope, with some anticipation, for a third installment in the series before too long. … Schott’s new novel is a hugely welcome one, and deserves to soar up the Christmas bestseller lists.”

“A glorious romp …

the book’s greatest strength is

its delicious verb fluency very

much in the mould of Wodehouse …

a splendidly jolly read.”

The Drones Club’s in peril.

Gussie’s in love.

Spode’s on the war-path.

Oh, and His Majesty’s Government needs a favour.

I say – it’s a good thing Bertie’s back!

In this eagerly anticipated sequel to Jeeves & The King of Clubs, Ben Schott leads Jeeves and Wooster on another elegantly uproarious espionage caper.

From the mean streets of Mayfair to the scheming spires of Cambridge, we encounter a joyous cast of characters: chiselling painters and criminal bookies, eccentric philosophers and dodgy clairvoyantes, appalling poets and pocket dictators, vexatious aunts and their vicious hounds.

But that’s not all:

Who is ICEBERG, and why is he covered in chalk?

Why is Jeeves reading Winnie-the-Pooh?

What is seven across and eighty-five down?

How do you play Russian Roulette at The Savoy?

All these questions, and more, are answered in Jeeves & The Leap of Faith – essential reading for fans of The Master.

Tinkety Tonk!

Purchase here

Click here for the crossword!

Smarter Than Your Average Drone?

— An appreciation of Bertie’s I.Q.

In writing Jeeves & The King of Clubs, I approached the keyboard not with a grand, personal vision, but as a deadly serious frivolity. My aim was to create a fabulous, literary ‘Heath Robinson machine’ – deploying all of the pulleys, levers, and lengths of knotted rope offered by the Wodehouse oeuvre to create the finest, funniest, and most charming Wooster homage possible.

I aspired to eschew caricature, pastiche, and (most banal of all) parody, to write in parallel with Plum: obeying the rules of his narrative style, deploying the linguistic traits of his characters, and respecting the rhythm of his magical prose.

Homage is not impersonation, however, and readers au fait with Plum’s ‘Woostershire’ will notice a few stylistic differences in Jeeves & The King of Clubs. There is, for example, a little more action and a tad less description, and Jeeves is, on occasion, given licence for short-hop flights of fanciful loquacity.

Moreover, since Wooster women tend to arrive in one of three varieties – simpering fools (Madeline Bassett), exacting harridans (Florence Craye), and brutal aunts (a sub-species of harridan) – it was joy to devise in Iona MacAuslan a wise, witty, and likeable heroine who might out-Ginger the nimblest of Rogers.

One observation made by a number of readers is that the Bertie of my homage is a little more quick-witted than some felt he was canonically. And so I hope readers will humour me if I explore this issue in a little detail.

The first thing to say is that I did not set out with any calculated plan to make Bertie significantly brainier. Indeed, to my mind, the idea that our hero is merely a drunken, hiccoughing imbecile is as erroneous as giving him a monocle.

It’s possible that the perception of an unredeemably dim-witted Bertie owes more to Hugh Laurie’s glorious portrayal in Clive Exton’s joyous ‘Jeeves and Wooster’ than Plum’s actual text where, lest we forget, in addition to winning the prize for Scripture Knowledge at Malvern House, Bertie attended Eton and graduated from Magdalen College, Oxford. Even in those days, such academic achievements were no cakewalk.

Second, it’s fair to ask whether someone as penetratingly sagacious (and eminently employable) as Reginald Jeeves would voluntarily spend some 60 years, 35 short stories, and 11 novels manning the soda-siphon for a complete fool. The elephant in this particular room is, of course, Jeeves’s overheard description of his employer in The Inimitable Jeeves:

‘You will find Mr Wooster,’ he was saying to the substitute chappie, ‘an exceedingly pleasant and amiable young gentleman, but not intelligent. By no means intelligent. Mentally he is negligible – quite negligible.’

Although it’s tempting to blame such acidity on the mal au foie that so grievously plagues Anatole, it’s hard not to admit that Jeeves is on to something, which brings me to point three . . .

In assessing Bertie’s intelligence – or lack of it – it’s vital to consider the caliber of his interlocutor. Compared to Jeeves, Bertie is indeed ‘mentally negligible’ – but then again, and here’s the nub, so are we all. Indeed it’s hard to think of any intellectual equal to the Oracle of Mayfair – excepting, perhaps, Mycroft Holmes or Baruch Spinoza.

Compared to Aunt Dahlia, I’d say Bertie is about par: the pair thrust and parry with equal dexterity, and although Dahlia usually gets the upper hand, this is more a reflection of pragmatic nepotic deference than intrinsic mateteral nouse.

And compared to his fellow Eggs, Beans, and Crumpets, Bertie soars above the pack. Within the intellectually hollowed halls of the Drones, Bertie is not merely primus inter pares but summa cum laude – if that’s the Latin I’m looking for.

So while Jeeves may well be correct in his assessment of Bertie’s mental negligibility, it’s a little like having one’s pizzicato critiqued by Paganini.

Point four speaks to what I consider to be the driving tension and creative genius at the heart of the Wooster canon: P.O.V.

All but two of the Jeeves and Wooster works are written from Bertie’s Point of View. And they are, by common consent compounded over a century, some of the deftest comic fiction ever inked. But how can this be, if Bertie is simply a buffoon?

No prose authored by an actual idiot would be bearable for more than a page or so – which doubtless explains why we’ve been spared the collected pensées of Charles ‘Biffy’ Biffen. And when the P.O.V. swings to Jeeves, in Bertie Changes His Mind, the effect, to my ear at least, is oddly discordant, and the prose is certainly no finer that when the guv’nor is wielding the pen.

Samuel Johnson recounts waking one morning mortified by a bad dream in which he had been bested in a battle of conversational wit. Only as the day progressed did Johnson realise that, since it was his dream, he had supplied both sides of the dialogue, including the winning lines of his imagined antagonist. Something similar is at work in the Wooster novels, where Bertie has an oxymoronically erudite awareness of his intellectual shortcomings.

This leads me to my final point: the small but significant question of self-deprecation. Notwithstanding the amour propre of a preux chevalier, Bertie is modest enough to admit that he is ‘no mastermind’ – which speaks to an insight absent from the true fool. Genuinely stupid people never doubt for a second that they possess anything less than genius – as illustrated only too starkly by the Spode-like chancers currently strutting across the global stage.

What minor modifications there may be to Bertie’s intellect, and other stylistic elements of the corpus, are the consequence of my desire to inject my homage with a shot of pith and pace. If you’ve ever seen the 1960 film Ocean’s 11 (with Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Sammy Davis Jr.) you’ll know that the 2001 remake (with George Clooney, Brad Pitt, and Matt Damon) is a little like chasing a biplane with Concorde.

Obviously, any such aggressive acceleration would ill-suit the sedate world of Wooster, but I felt that any scenario in which Bertie becomes a British spy might benefit from a glug or two of Buck-U-Uppo, if not Brinkley Sauce.

— This is an extract of an essay published in Wooster Sauce.